Part 1: The Hardware Product Lifecycle

Serge Dougoud

Serge Dougoud is a high-tech staff program manager with a proven track record of directing large programs in innovative companies, overseeing projects from concept to mass production. With extensive experience in marketing product management, R&D design and development, and manufacturing (including process, procurement, production, and supply chain), Serge has held key roles at Hewlett-Packard and co-founded start-ups in printing and CRM.

With a passion for guiding individuals and technology organizations, Serge advocates for the best processes in a fun and collaborative manner. He holds a Master’s in Mechanical and Materials Engineering from Ecole Polytechnique Federale de Lausanne, Switzerland (Swiss Institute of Technology), a YMP Certification from INSEAD, and is a Certified Coach and Neuro-linguistic Master Practitioner. Serge is widely recognized as the “PLC Guru” (Product Life Cycle).

In the fiercely competitive world of PC manufacturing, I once played a pivotal role at a large multi-billion-dollar company. We embarked on a memorable journey, climbing from the fifth position to becoming the market leader in a few short years. As you can imagine, even though it was a success for our bottom line, the chaotic day-to-day road to get there was not exactly my idea of a dream work life.

Our organization faced many challenges due to rapid growth, including technical roadblocks, logistical nightmares, and complex interpersonal dynamics. However, our main challenge was Time to Market (TTM). We realized the business could not compete effectively if every product launch reached the market months after our competitors.

The math was simple: three months of lost revenue on a product with a 12-18 month shelf life kept us out of the race and prevented us from gaining market share despite the product’s strengths. The question was how to outpace rivals with twice our R&D budget and the purchasing power to achieve lower costs. How could we break out of this vicious cycle?

In the early days of computer hardware in the 1990s, our company needed 18 months to build a personal computer from design to manufacturing release (or FCS). We reduced our development time to just 6 months, only five years later. We did this by embracing Agile methods and ideas. Read on to learn how we did it.

The Hardware Product Lifecycle

First, on the technical side, we learned a lot from the automotive industry to design by platform and module, reusing or at least leveraging as many components as possible from one product to another. Next, by working cross-functionally, we were able to make quick decisions involving people working across global divisions without involving senior leadership, provided these decisions were within the approved project scope. Finally, by breaking down silos, we transformed our processes, ensuring that agility and efficiency were not just buzzwords but the heartbeat of our operations.

However, our success was not based on technical capabilities alone. We had a secret weapon: a Product Life Cycle (PLC) process. The PLC is a series of stages — like a roadmap — with milestones that transformed our ideas into products manufactured at scale. The PLC was more than a list of steps or check boxes; rather, it was a principle we lived by.

Following the process enabled us to build a repository of institutional knowledge and increase our efficiency and aptitude for the next project. This way of working has now become a staple in successful high-tech companies, but at the time, it was a new way of working.

■ Product Division (Business Unit) ■ Regional Sales Business Units

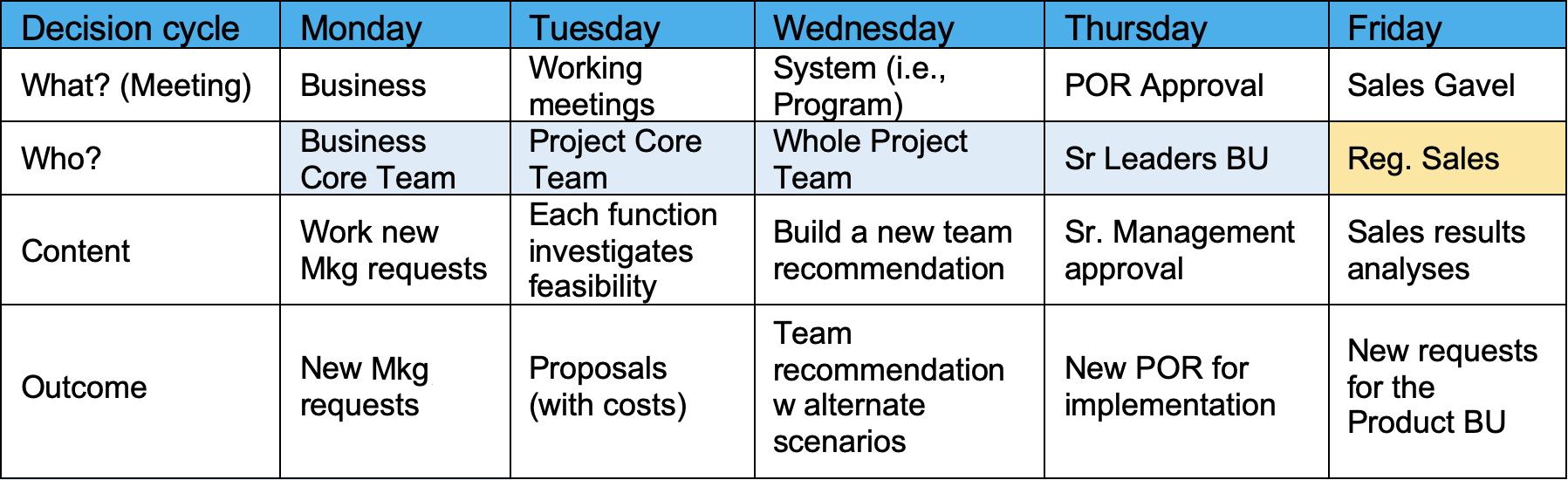

Step by step, through each phase of the PLC, we completed the deliverables for each milestone. Strictly speaking, pure “Agile” may not fit a hardware context, so I prefer to use the term “agility.” Nonetheless, the tentpoles of our methods were our weekly review of the business needs and corrective action. This approach applied equally to our sustaining and NPI products. The table shows an example of our weekly decision cycle and sequence.

Our highly dynamic consumer market drove this weekly frequency, but the tempo could vary for other industries. Less dynamic businesses could use a bi-monthly or monthly review cycle.

The keys in this process were threefold:

- Strategic Segregation: We meticulously separated three types of conversations 1.) the business discussions (needs) from 2.) the tactical implementation discussions (build a plan) and 3.) the decision-making meetings.

- Agenda Adherence: Each meeting followed a precise agenda with clear objectives.

- Recurrent Scheduling: We set up recurring placeholder meetings in stakeholders’ calendars. The message was clear: the project doesn’t stop for travel or absence. Representation was key.

Why such rigidity, you ask? Many senior leaders miss the excitement of their previous SME job and would love to jump into a technical or financial discussion! This tendency, although well-intentioned, can derail a meeting, transforming a well-prepared session into an impromptu exploration of technical trivia, thus killing your agenda and the meeting outcome. Sound familiar?

The Decision-Making Process

Even a strong program manager has a hard time interrupting these captivating off-topic diversions and getting the meeting back on track. Ego can be useful in leadership but becomes a liability when it disrupts the experts from getting the actual work done!

The key to success is the speed and agility of the decision-making process. It requires participants to acknowledge that everyone has a critical role (beginner and senior alike). It also requires team members to clarify and align on who has the power to make which decisions. While questioning or challenging ideas is fair game, overstepping into another’s area of responsibility is not. This principle ensures that each voice, responsible for its own domain, is heard and better decisions result.

Agile decision-making is a practice I still apply to my work. Even the most meticulous project schedule can exceed deadlines without a structured decision-making process. For instance, getting the right execs together for a decision can take a couple of weeks. Other times, we hope that time will fix the issue without making a decision. (It eventually does, but too late!)

Surprisingly, finding an engineering solution to a technical challenge was relatively easy. Anticipating the problem and identifying the right resources made it possible to overcome even extremely complex engineering problems. We had a talented engineering team.

The limiting factor was getting buy-in from people and agreeing to make the best decision on time and only once. We tried to make the best decision with the information available and got comfortable with not making an ideal decision that could only become apparent weeks later.

Conclusion

Managing the hardware product lifecycle in an intentionally structured way with a weekly business review and a clear process for making decisions is a strong start. Still, it overlooks a crucial aspect of operationalizing these changes: managing people. Part 2 explores the delicate art of managing people and projects.

—

Are you curious how to decrease your Time to Market (TTM)? Contact us for a free consultation today. Or read on and learn more about Agile hardware development from the experts at Product Realization Group.